MEGAN KANKA (Megan's Law) - 7 yo (7/1994) - / Convicted: Jesse Timmendequas - Trenton, NJ

Page 1 of 1

MEGAN KANKA (Megan's Law) - 7 yo (7/1994) - / Convicted: Jesse Timmendequas - Trenton, NJ

MEGAN KANKA (Megan's Law) - 7 yo (7/1994) - / Convicted: Jesse Timmendequas - Trenton, NJ

EXCLUSIVE: Parents of little girl who inspired Megan's Law recall brutal rape, murder of their daughter 20 years later

Megan Kanka was raped and strangled by a twice-convicted sex offender across the street from her home in Hamilton Township, N.J., in July of 1994. Her parents, Maureen and Richard Kanka, pushed tirelessly for the law that alerts parents when a sexual predator moves into the neighborhood. Two decades later, the family is still haunted by the tragedy.

BY Rich Schapiro

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

Sunday, July 27, 2014, 2:30 AM

Parents Of Victim Who Inspired Megan's Law Reflect On The 20th...

NY Daily News

MEGAN27N by Pearl Gabel and Stephanie Keith

Parents Of Victim Who Inspired Megan's Law Reflect On The 20th Anniversary Of Her Death

MEGAN27N by Pearl Gabel and Stephanie Keith

Megan's mom tries to avoid looking out the bay window of her home in leafy Hamilton Township, N.J.

Across the street sits a tiny memorial park full of pink and yellow lilies and bright red rose bushes. The serene space used to comfort her.

But 20 years after the darkest day of her life, she doesn’t see the landscaped grass and blooming flowers when she gazes across the street.

She sees the home that once stood there – the two-story house with white aluminum siding where a twice-convicted sex offender raped and strangled her 7-year-old daughter.

“In my mind’s eye, it’s always there,” Megan’s mom says. “Always.”

Megan is Megan Kanka, the tragic New Jersey girl who inspired the law that alerts parents when a sexual predator moves into the neighborhood.

AP

AP

Megan was raped and strangled to death by a twice-convicted sex offender who lived across the street.

To most of the country, she’s only a name.

To her parents, she’s little Maggie, the sweet-faced girl whose murder turned their lives upside down and has left them emotionally scarred two decades later.

“Maggie is so missed,” Maureen Kanka says, sitting in the front room of her house beside her husband, Richard.

“She was a little me. We were so close. I didn’t know if I was going to make it, to be honest with you. I wanted to be dead for a couple years. I wanted to die.”

It was a lazy summer Friday – July 29, 1994.

At about 6:30 p.m., Megan hopped on her bike and went for a ride around her quiet block just outside of Trenton.

The soon-to-be second-grader had friends living all around the neighborhood.

She’d often stop to pet the neighborhood dogs through backyard fences. Sometimes, she’d come back carrying a handful of flowers for her mother that she had picked from neighbors’ yards.

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

Megan Kanka’s parents, Maureen and Richard, look out the window of their New Jersey home on the site that held the house where their daughter was killed in 1994.

But this time, Megan never returned home.

The Kankas frantically searched the neighborhood and then called cops.

“I can still see Richie walking over here and saying he couldn’t find his daughter,” recalls John Devlin, 79, who lives next door to the Kankas. “It was a terrible thing.

“And when they found her,” Devlin adds, “it was hell.”

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

Days after the murder, Richard and Maureen Kanka decided to devote their lives to exposing child predators who were living undetected in American neighborhoods, and they pushed for passage of Megan's Law.

Megan’s battered body was discovered the next day inside a toy box dumped in a nearby park.

By then, the monster responsible for Megan’s killing had already confessed.

His name was Jesse Timmendequas. He was a neighbor they rarely spoke to – quiet, awkward and carrying a dark secret.

The 33-year-old Timmendequas told cops he lured Megan into his home by promising to show her his new puppy. Then he led her to his upstairs bedroom, where he beat, raped and strangled her.

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

In Maureen Kanka's collection of angels stands a portrait of Megan from around the time of her death at 7 years old. .

After Timmendequas dumped the body, he even joined the massive search for Megan. But Timmendequas later broke in a police interview and led cops to the body.

Already reeling from Megan’s murder, the Kankas soon received more shocking news. Timmendequas was a paroled sex offender who was sharing his house with two other child molesters.

Quote:Didn’t anybody know that three convicted sex offenders lived across the street? It turned out nobody knew.They had no idea three child predators were living across the street from where they were raising Megan and their two other kids – Jeremy, then 9, and Jessica, then 11.

“We were outraged,” Richard Kanka says. “We wanted to know if the police knew about this. Didn’t anybody know that three convicted sex offenders lived across the street? It turned out nobody knew.”

The crime shook the nation.

Plunged into unimaginable grief, the Kankas grappled with how to soldier on.

Just days after the murder, they made a decision: They were going to dedicate their lives to exposing child predators living undetected in American neighborhoods.

TONY KURDZUK/AP

TONY KURDZUK/AP

Jesse Timmendequas confessed to the crime and was sentenced to death in 1996. His sentence was commuted to life in prison without the possibility of parole when New Jersey abolished its death penalty.

Megan’s parents traveled around the country, prodding politicians, lecturing parents and giving hundreds of press interviews.

“It was so chaotic, and it was so traumatic,” Maureen Kanka recalls. “I went from being a mother to being in the spotlight . . . For years, I couldn’t even go to the cemetery without people coming up to me.”

Money poured into the Megan Nicole Kanka Foundation, and results came quickly. Three months after the murder, New Jersey passed Megan’s Law, which requires the whereabouts of high-risk sex offenders to be made public.

The law became the model for a federal statute passed two years later. A parade of other states, including New York, soon created their own versions.

The legislative victories were satisfying, but the Kankas couldn’t escape a gnawing sadness. At night, their children had horrible nightmares.

Richard and Maureen sometimes found Jeremy screaming inside his closet in the middle of the night. One of Jessica’s nightmares was particularly haunting.

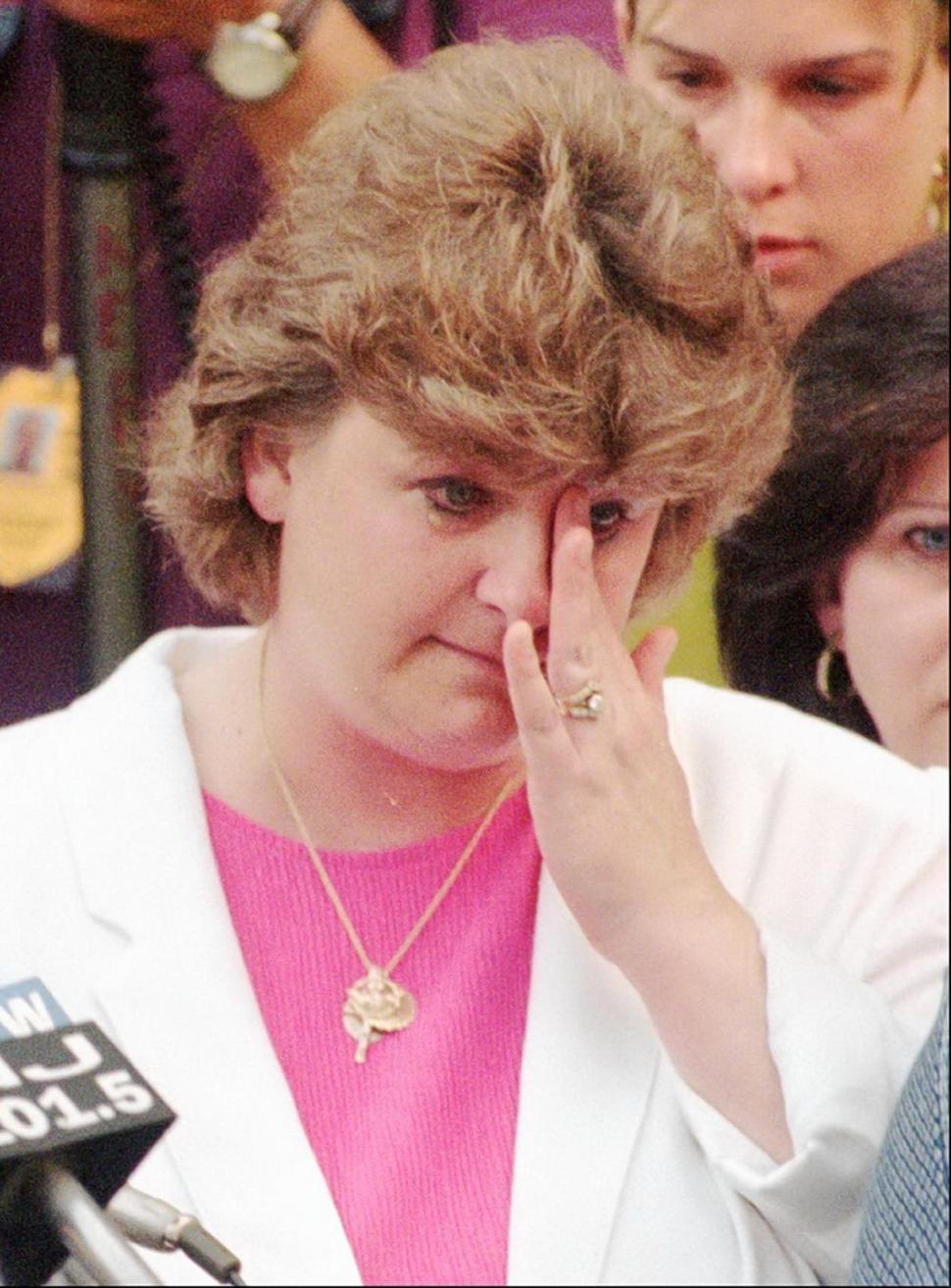

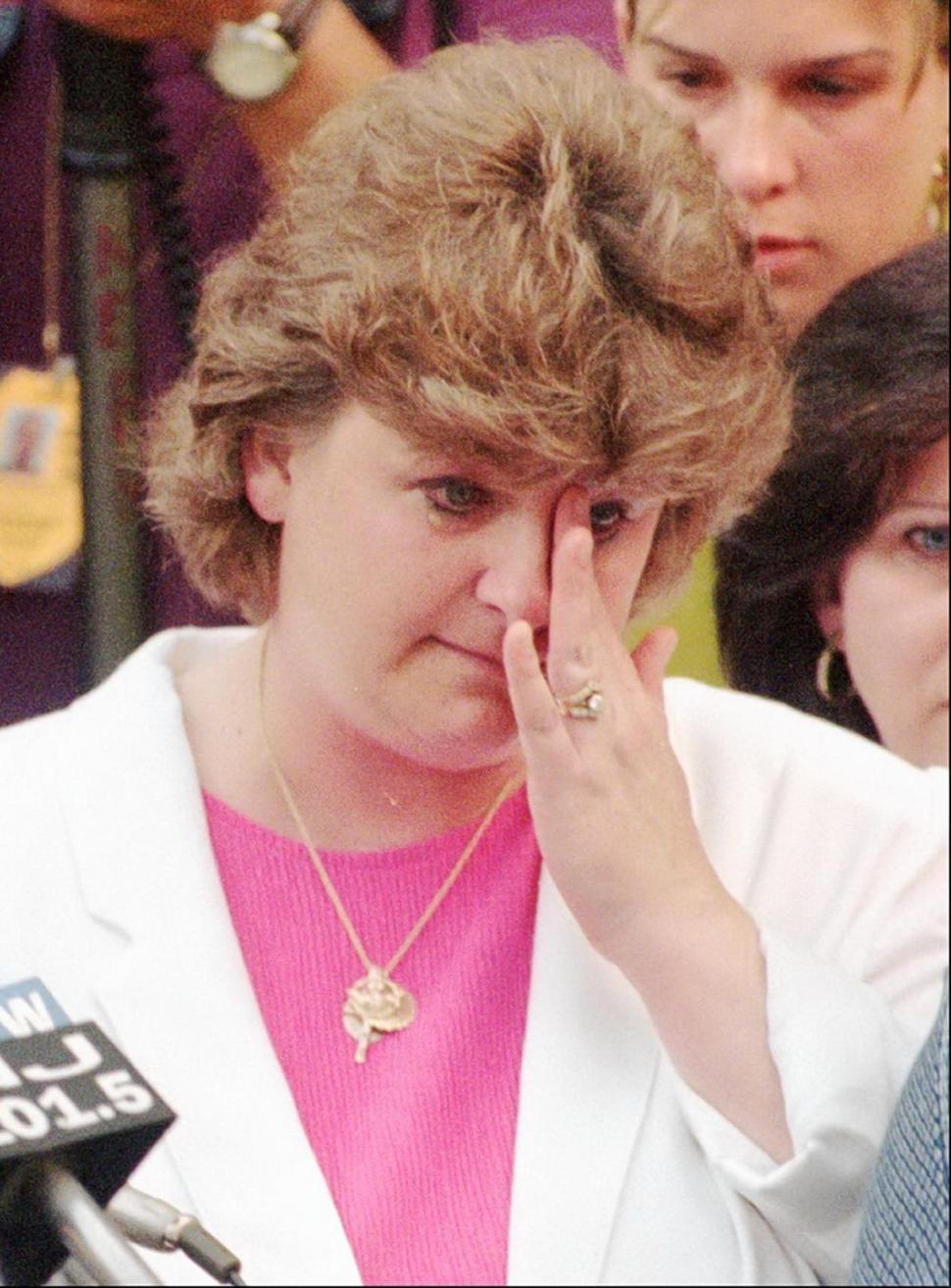

CHARLES REX ARBOGAST/AP

CHARLES REX ARBOGAST/AP

Maureen Kanka wipes a tear from her eye outside the courthouse in Trenton, N.J., in 1997 after a jury ordered the death penalty for Jesse Timmendequas.

“Megan came to me in my dreams and she showed me what happened,” Jessica told them one day, her mother recalls. “I was standing in the doorway of that room, and I saw everything that happened. I couldn’t wake up. I couldn’t move.”

Maureen Kanka remained fixated on the room for months. Before Timmendequas’ house was razed, she convinced a detective to let her inside.

When she stepped into the cramped bedroom, she felt “a tingling all over my body.”

“It was so strong I had to sit down on the bed,” Maureen Kanka says. “I think she hugged me in that room. I had complete closure.”

Timmendequas was convicted on all charges and sentenced to death in June 1997.

“It is the ultimate justice that we can bring to the memory of our little girl,” Maureen Kanka said at the time. “Megan was worth a life.”

Timmendequas remained on Death Row until Dec. 17, 2007, when New Jersey abolished its death penalty. His sentence was commuted to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

“That was a real slap in the face,” Richard Kanka says.

HARRY HAMBURG/KRT

HARRY HAMBURG/KRT

Maureen and Richard Kanka are seen in 1996 with daughter Jessica and son Jeremy as President Bill Clinton signs 'Megan’s Law.'

Even then, 13 years after the crime, the Kankas felt like they were living under a dark cloud. Maureen Kanka got through the days by taking antidepressants. Richard Kanka distracted himself through his work as a mechanical contractor.

He’d spend nights and weekends organizing the finances of their foundation and volunteering for multiple causes.

Whenever any child disappeared in New Jersey, Richard Kanka showed up to help in the search. On the day after the 9/11 attacks, union officials asked for volunteers to help in the recovery effort. Hours later, he was on a boat crossing the Hudson River with a group of colleagues. They were ultimately instructed to help stage supplies in Jersey City.

“I look at how the people helped us,” Richard Kanka says.

“When we walked around that night, there were literally thousands of people looking for Maggie. Maybe that just changed my whole thought process around.

TONY KURDZUK/AP

TONY KURDZUK/AP

Richard Kanka gives his victim’s impact statement at the trial of the killer.

“We had so much given to us,” Kanka adds. “Whenever somebody asks me, I can’t say no. Whenever they ask me, I’ll be there.”

But Maureen’s nonstop advocacy and Richard’s nonstop work schedule began to take a toll. They went 11 years without taking a vacation. In fact, they rarely did anything for pleasure.

The foundation had been moving forward with a federal grant that allowed it to fund background checks for volunteers working with kids.

But by 2013, the grant money had run out. For the first time in 19 years, Maureen Kanka had no resources to sustain her mission.

To keep going, she would have had to solicit donations from private companies. But she was exhausted. All those months on the road, all that time spent defending the law.

“I wore out,” Maureen Kanka says. “I took a break. I had never stopped from anything.”

Stephanie Keith for new york daily news

Stephanie Keith for new york daily news

The crime scene, across the street from the Kankas' house in Hamilton Township, N.J., has been turned into a memorial park.

But what she thought would be a welcome respite turned out to be a sort of prison. Now there was nothing to distract her from fixating on what happened to Megan. Once again, she fell into a deep depression.

“Being idle was too much,” she says. “It didn’t do well for me . . . I kind of wish I had more grant money.”

Quote :He took so much from us. I’m not going to let him take any more.The newest member of the Kanka family has raised everyone’s spirits. Twice a week, Maureen watches her 2-year-old grandson, Zachary. “He’s the apple of my eye,” she says. “He’s a lifesaver, that kid.”

To this day, they never utter the name of the man who took the life of their youngest child.

“I never think about him,” Maureen Kanka says. “He took so much from us. I’m not going to let him take any more.”

She’s now working on a book about her daughter and the movement sparked by her death.

Stephanie Keith for new york daily news

Stephanie Keith for new york daily news

A plaque in the park honors Megan. The Kanka home can be seen in the background.

“Had she lived, I have no doubt she would have done great things,” Maureen Kanka says.

“You think, she could be married now, have kids,” she adds, her voice trailing off.

The Kankas still wonder if they made the right decision by staying in their house. But they have no regrets over the crusade they’ve led over the past two decades.

“We sacrificed a lot, hopefully to save a lot,” says Richard Kanka.

“I know we made an impact,” Maureen Kanka says. “I hope it was enough. It was the best that we were able to do, let’s put it that way.”

She pauses for a moment. “I just hope it was enough for some kids.”

http://www.nydailynews.com/news/crime/parents-girl-inspired-megan-law-recall-tragedy-article-1.1881551#ixzz38fXiBoVj

Megan Kanka was raped and strangled by a twice-convicted sex offender across the street from her home in Hamilton Township, N.J., in July of 1994. Her parents, Maureen and Richard Kanka, pushed tirelessly for the law that alerts parents when a sexual predator moves into the neighborhood. Two decades later, the family is still haunted by the tragedy.

BY Rich Schapiro

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

Sunday, July 27, 2014, 2:30 AM

Parents Of Victim Who Inspired Megan's Law Reflect On The 20th...

NY Daily News

MEGAN27N by Pearl Gabel and Stephanie Keith

Parents Of Victim Who Inspired Megan's Law Reflect On The 20th Anniversary Of Her Death

MEGAN27N by Pearl Gabel and Stephanie Keith

Megan's mom tries to avoid looking out the bay window of her home in leafy Hamilton Township, N.J.

Across the street sits a tiny memorial park full of pink and yellow lilies and bright red rose bushes. The serene space used to comfort her.

But 20 years after the darkest day of her life, she doesn’t see the landscaped grass and blooming flowers when she gazes across the street.

She sees the home that once stood there – the two-story house with white aluminum siding where a twice-convicted sex offender raped and strangled her 7-year-old daughter.

“In my mind’s eye, it’s always there,” Megan’s mom says. “Always.”

Megan is Megan Kanka, the tragic New Jersey girl who inspired the law that alerts parents when a sexual predator moves into the neighborhood.

AP

APMegan was raped and strangled to death by a twice-convicted sex offender who lived across the street.

To most of the country, she’s only a name.

To her parents, she’s little Maggie, the sweet-faced girl whose murder turned their lives upside down and has left them emotionally scarred two decades later.

“Maggie is so missed,” Maureen Kanka says, sitting in the front room of her house beside her husband, Richard.

“She was a little me. We were so close. I didn’t know if I was going to make it, to be honest with you. I wanted to be dead for a couple years. I wanted to die.”

It was a lazy summer Friday – July 29, 1994.

At about 6:30 p.m., Megan hopped on her bike and went for a ride around her quiet block just outside of Trenton.

The soon-to-be second-grader had friends living all around the neighborhood.

She’d often stop to pet the neighborhood dogs through backyard fences. Sometimes, she’d come back carrying a handful of flowers for her mother that she had picked from neighbors’ yards.

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily NewsMegan Kanka’s parents, Maureen and Richard, look out the window of their New Jersey home on the site that held the house where their daughter was killed in 1994.

But this time, Megan never returned home.

The Kankas frantically searched the neighborhood and then called cops.

“I can still see Richie walking over here and saying he couldn’t find his daughter,” recalls John Devlin, 79, who lives next door to the Kankas. “It was a terrible thing.

“And when they found her,” Devlin adds, “it was hell.”

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily NewsDays after the murder, Richard and Maureen Kanka decided to devote their lives to exposing child predators who were living undetected in American neighborhoods, and they pushed for passage of Megan's Law.

Megan’s battered body was discovered the next day inside a toy box dumped in a nearby park.

By then, the monster responsible for Megan’s killing had already confessed.

His name was Jesse Timmendequas. He was a neighbor they rarely spoke to – quiet, awkward and carrying a dark secret.

The 33-year-old Timmendequas told cops he lured Megan into his home by promising to show her his new puppy. Then he led her to his upstairs bedroom, where he beat, raped and strangled her.

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily News

Stephanie Keith for New York Daily NewsIn Maureen Kanka's collection of angels stands a portrait of Megan from around the time of her death at 7 years old. .

After Timmendequas dumped the body, he even joined the massive search for Megan. But Timmendequas later broke in a police interview and led cops to the body.

Already reeling from Megan’s murder, the Kankas soon received more shocking news. Timmendequas was a paroled sex offender who was sharing his house with two other child molesters.

Quote:Didn’t anybody know that three convicted sex offenders lived across the street? It turned out nobody knew.They had no idea three child predators were living across the street from where they were raising Megan and their two other kids – Jeremy, then 9, and Jessica, then 11.

“We were outraged,” Richard Kanka says. “We wanted to know if the police knew about this. Didn’t anybody know that three convicted sex offenders lived across the street? It turned out nobody knew.”

The crime shook the nation.

Plunged into unimaginable grief, the Kankas grappled with how to soldier on.

Just days after the murder, they made a decision: They were going to dedicate their lives to exposing child predators living undetected in American neighborhoods.

TONY KURDZUK/AP

TONY KURDZUK/APJesse Timmendequas confessed to the crime and was sentenced to death in 1996. His sentence was commuted to life in prison without the possibility of parole when New Jersey abolished its death penalty.

Megan’s parents traveled around the country, prodding politicians, lecturing parents and giving hundreds of press interviews.

“It was so chaotic, and it was so traumatic,” Maureen Kanka recalls. “I went from being a mother to being in the spotlight . . . For years, I couldn’t even go to the cemetery without people coming up to me.”

Money poured into the Megan Nicole Kanka Foundation, and results came quickly. Three months after the murder, New Jersey passed Megan’s Law, which requires the whereabouts of high-risk sex offenders to be made public.

The law became the model for a federal statute passed two years later. A parade of other states, including New York, soon created their own versions.

The legislative victories were satisfying, but the Kankas couldn’t escape a gnawing sadness. At night, their children had horrible nightmares.

Richard and Maureen sometimes found Jeremy screaming inside his closet in the middle of the night. One of Jessica’s nightmares was particularly haunting.

CHARLES REX ARBOGAST/AP

CHARLES REX ARBOGAST/APMaureen Kanka wipes a tear from her eye outside the courthouse in Trenton, N.J., in 1997 after a jury ordered the death penalty for Jesse Timmendequas.

“Megan came to me in my dreams and she showed me what happened,” Jessica told them one day, her mother recalls. “I was standing in the doorway of that room, and I saw everything that happened. I couldn’t wake up. I couldn’t move.”

Maureen Kanka remained fixated on the room for months. Before Timmendequas’ house was razed, she convinced a detective to let her inside.

When she stepped into the cramped bedroom, she felt “a tingling all over my body.”

“It was so strong I had to sit down on the bed,” Maureen Kanka says. “I think she hugged me in that room. I had complete closure.”

Timmendequas was convicted on all charges and sentenced to death in June 1997.

“It is the ultimate justice that we can bring to the memory of our little girl,” Maureen Kanka said at the time. “Megan was worth a life.”

Timmendequas remained on Death Row until Dec. 17, 2007, when New Jersey abolished its death penalty. His sentence was commuted to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

“That was a real slap in the face,” Richard Kanka says.

HARRY HAMBURG/KRT

HARRY HAMBURG/KRTMaureen and Richard Kanka are seen in 1996 with daughter Jessica and son Jeremy as President Bill Clinton signs 'Megan’s Law.'

Even then, 13 years after the crime, the Kankas felt like they were living under a dark cloud. Maureen Kanka got through the days by taking antidepressants. Richard Kanka distracted himself through his work as a mechanical contractor.

He’d spend nights and weekends organizing the finances of their foundation and volunteering for multiple causes.

Whenever any child disappeared in New Jersey, Richard Kanka showed up to help in the search. On the day after the 9/11 attacks, union officials asked for volunteers to help in the recovery effort. Hours later, he was on a boat crossing the Hudson River with a group of colleagues. They were ultimately instructed to help stage supplies in Jersey City.

“I look at how the people helped us,” Richard Kanka says.

“When we walked around that night, there were literally thousands of people looking for Maggie. Maybe that just changed my whole thought process around.

TONY KURDZUK/AP

TONY KURDZUK/APRichard Kanka gives his victim’s impact statement at the trial of the killer.

“We had so much given to us,” Kanka adds. “Whenever somebody asks me, I can’t say no. Whenever they ask me, I’ll be there.”

But Maureen’s nonstop advocacy and Richard’s nonstop work schedule began to take a toll. They went 11 years without taking a vacation. In fact, they rarely did anything for pleasure.

The foundation had been moving forward with a federal grant that allowed it to fund background checks for volunteers working with kids.

But by 2013, the grant money had run out. For the first time in 19 years, Maureen Kanka had no resources to sustain her mission.

To keep going, she would have had to solicit donations from private companies. But she was exhausted. All those months on the road, all that time spent defending the law.

“I wore out,” Maureen Kanka says. “I took a break. I had never stopped from anything.”

Stephanie Keith for new york daily news

Stephanie Keith for new york daily newsThe crime scene, across the street from the Kankas' house in Hamilton Township, N.J., has been turned into a memorial park.

But what she thought would be a welcome respite turned out to be a sort of prison. Now there was nothing to distract her from fixating on what happened to Megan. Once again, she fell into a deep depression.

“Being idle was too much,” she says. “It didn’t do well for me . . . I kind of wish I had more grant money.”

Quote :He took so much from us. I’m not going to let him take any more.The newest member of the Kanka family has raised everyone’s spirits. Twice a week, Maureen watches her 2-year-old grandson, Zachary. “He’s the apple of my eye,” she says. “He’s a lifesaver, that kid.”

To this day, they never utter the name of the man who took the life of their youngest child.

“I never think about him,” Maureen Kanka says. “He took so much from us. I’m not going to let him take any more.”

She’s now working on a book about her daughter and the movement sparked by her death.

Stephanie Keith for new york daily news

Stephanie Keith for new york daily newsA plaque in the park honors Megan. The Kanka home can be seen in the background.

“Had she lived, I have no doubt she would have done great things,” Maureen Kanka says.

“You think, she could be married now, have kids,” she adds, her voice trailing off.

The Kankas still wonder if they made the right decision by staying in their house. But they have no regrets over the crusade they’ve led over the past two decades.

“We sacrificed a lot, hopefully to save a lot,” says Richard Kanka.

“I know we made an impact,” Maureen Kanka says. “I hope it was enough. It was the best that we were able to do, let’s put it that way.”

She pauses for a moment. “I just hope it was enough for some kids.”

http://www.nydailynews.com/news/crime/parents-girl-inspired-megan-law-recall-tragedy-article-1.1881551#ixzz38fXiBoVj

twinkletoes- Supreme Commander of the Universe With Cape AND Tights AND Fancy Headgear

- Job/hobbies : Trying to keep my sanity. Trying to accept that which I cannot change. It's hard.

Similar topics

Similar topics» JOSETTE WRIGHT -12 yo - (1994) /Convicted: Anthony DiPippo - Carmel CA

» BRANDON BAUGH - 3 months (1994) : Convicted - Cathy Lynn Henderson, Gatesville, TX

» KIMBERLY WATERS - 11 yo (1994) - / Convicted: Mother's ex; Eddie Wayne Davis - Lakeland FL

» MEGAN MAXWELL - 19 yo (2009)/ Convicted: Jeffrey Lee Stock - Cocke TN

» MICHAEL and ALEX SMITH - 3 yo and 14 months (1994) - Spartanburg SC

» BRANDON BAUGH - 3 months (1994) : Convicted - Cathy Lynn Henderson, Gatesville, TX

» KIMBERLY WATERS - 11 yo (1994) - / Convicted: Mother's ex; Eddie Wayne Davis - Lakeland FL

» MEGAN MAXWELL - 19 yo (2009)/ Convicted: Jeffrey Lee Stock - Cocke TN

» MICHAEL and ALEX SMITH - 3 yo and 14 months (1994) - Spartanburg SC

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

Home

Home